- Home

- Latifa Ali

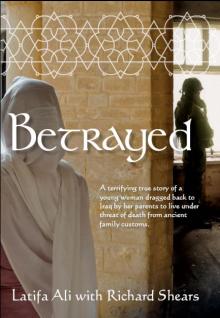

Betrayed Page 10

Betrayed Read online

Page 10

I was told what to do. At midday the following day, when I knew my aunt would be in another part of the city, and having obtained Zana’s approval, I was picked up by David’s driver in a white UN car with the initials in blue on the side. Zana came to the door and watched as I got in. He must have been impressed, particularly as he thought I was going to pick up some paperwork for him regarding the pipeline project.

David’s house was a large white two-storey building with a UN flag flying over the front gate and another on the roof. As instructed, I did not go in through the front entrance but was directed by the driver to a way in through the kitchen at the rear. If anyone saw me going in, they would hopefully think that I was one of the kitchen staff. An Assyrian housekeeper, as usual without a hijab for they are Catholics, was busy in the kitchen and nodded a greeting towards me. There would be no chance of gossip by her, for the Assyrians were far more ‘Westernised’.

David was waiting for me, dressed casually in an open-neck white shirt. He invited me to sit on a sofa and asked if I would like coffee. He apologised that it was only Nescafe. Only Nescafe! I hadn’t seen or tasted it since leaving Germany and I welcomed the offer. He sat opposite me as we danced around with words, discovering that we had exactly the same birthday. If that was not an omen, I did not know what was. Then I brought the subject around to explaining how much I wanted to return to Australia but there was no-one who could help me because I did not even have a passport. I told him, however, that I had all my passport details written on that piece of paper.

‘I’ll do what I can to help you, Latifa,’ he said. ‘I’m sure I’ll be able to do something to get you out of here.’

I wondered if I had told him enough to convince him of the urgency for me to leave. Dare I tell him the real reason—that I was not a virgin and that would bring about my death, like it had so many other young women?

Without further thought, I began telling him.

‘David, you must keep this to yourself but there is a very strong reason why I must leave,’ I began.

He sat back in his chair without comment, waiting for me to go on.

‘You see, I am not a virgin. It happened in Germany. A passionate moment turned into a rape. I didn’t want it to happen but the fact is, it did.’

He brought a closed hand to his face, his forefinger against his cheekbone, absorbed in my ‘confession’.

‘I see,’ he said. Then he sat in silence for a short while, just staring at me. I felt compelled to tell him that it was my very own cousin who had raped me, but I stopped myself. Surely he did not need to know any more.

Finally he said: ‘You are indeed in a very dangerous situation. It hasn’t escaped me how eligible you are. You must have had every man in town after you. It can only be a matter of time before your father lines you up with someone.’

‘And that will be the end of me.’

I told him about my cousin who had been driven out into the desert and killed. I also relayed to him the story I had heard in Germany of a Kurdish woman called Pele, living in Sweden, who had campaigned against honour killings. She began a relationship with a Swedish man and when she returned to Dohuk in 1999 for a holiday, she was shot dead by her uncle because he believed she had brought shame to the family.

He shook his head. ‘No, Latifa, I won’t let that happen to you. I’ll do everything in my power to get you away. That’s a promise.’

I wanted to leap up and throw myself on him and hug him and thank him, for he was the first person who had said anything like that. There was an infectious charm about him and I felt I could trust him. He was the UN, for heaven’s sake. If I couldn’t trust him, then who could I trust?

I had to leave. I already feared I had been away too long. He gave me some documents to take back with me concerning the pipeline project—a more detailed map of the area where the project would start and it would be enough to give to Zana—and when we stood, he gave me a peck on the cheek. He took my hand and I took his. I looked deep into his eyes and thought: ‘Don’t betray me, David. Don’t betray me like the others.’

I managed to go to his house three more times over the following weeks on the pretext of picking up more plans for the pipe project and our personal relationship blossomed, so that each time I left him we embraced with a passionate kiss, but it went no further than that. Each time I was with him, I forgot all about my troubles. I enjoyed his company, his touch, so much and I knew that I was falling for him. But while I believed our burgeoning relationship was a secret between us—and when I say relationship, I’m talking about a total of three snatched hours at that stage!—Zana, smart, intelligent, watchful Zana, had already seen how attracted David was to me. There had been that initial meeting in the UN board room, the visit to the pipeline site, the lunch. Then there were my trips to pick up more documents. Zana read through the bluff perfectly.

One day he called me into his office and closed the door.

‘Latifa, I want to talk to you about David,’ he said. I felt a lump come to my throat. He knew! He knew what I’d been up to. But what he said came as such a shock that I remained speechless.

‘I want you to work on a mission for us,’ he said. I correctly assumed that ‘us’ meant he and the owner. ‘I know what’s going on with you and him and I think you can be of assistance to us.’

‘What do you mean?’

His eyes met mine as he sat back in his chair, slouching in a way that his stomach stuck out, and he lit up a cigarette. He appeared to be composing his words before he finally spoke.

‘I want you to secretly get some important information from the UN for us,’ he said.

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. It had to be some kind of joke. I didn’t reply. I just sat staring at him.

‘You are probably aware of your mother’s work for us,’ he continued. ‘She has been a faithful servant for Kurdistan. She had all the attributes and you, of course, are your mother’s daughter. Men are falling over you—don’t worry, I’ve seen it—you speak English, you speak Kurdish and you are intelligent.’

There was that phrase again—’your mother’s daughter.’ It had been used against me by my grandmother and now it was being used—favourably?—to encourage me to be… a spy?

‘As you know, Latifa, we have struggled for decades for our independence here in Kurdistan, to be totally free of the dangerous regime of Saddam Hussein. Along the way, our people have been murdered and at the very least persecuted. Our towns and villages have been ransacked and you will know about the gassing of hundreds of our people just a few years ago. We are supposed to receive protection and aid from the UN—and you know better than anyone that they are represented here.’

He gave me a long look as he said that. Had I been followed to David’s home? His stare sent a wave of unease through my body.

‘At every opportunity our people are leaving, looking for a new life in the West because they fear that Saddam Hussein has not finished yet.’

People might be leaving, I thought, but not me. I had no documents. I was a nobody.

I finally found my tongue. I had hardly taken in what he had been saying aside from a few words… spy… people leaving…

‘You want me to be a spy?’

He slowly nodded.

‘Are you crazy? What do I know about spying? And who do you want me to spy on?’ Although even as I asked the question I knew what his answer was going to be.

He exhaled and watched the smoke rise.

‘David,’ he said.

‘You’re crazy. I’m not going to spy on anyone.’ Particularly David, I thought. He was my ticket out of this cursed place.

‘If you do this for us,’ he said, ‘I promise I will help you to go home.’

Another promise! Another offer of help to leave. Who was I to believe?

He read the disbelief on my face. ‘There are people I know who have only to snap their fingers and all the doors will be opened for you. But they won’t do it unless

you give something in return.’

‘Zana,’ I said. ‘All I’ve heard in the past months are lies. I’ve been betrayed by my own mother, I’ve been physically abused by my own father, I’ve had men leering at me like sex-hungry dogs and I’ve been locked up like a prisoner. I don’t belong here. I might be a child of Kurdistan but I’m also an Australian. My home is Sydney, not Dohuk. You have no claim on me to work for you or your government.’

He was silent for a moment. ‘We are your only way out,’ he said at last.

But David had promised to help me, too. Yet I was being asked to spy on him. Whose side should I take? Whose promises of help were real?

‘What are you asking me to do?’

Zana stood and began pacing his office. ‘We want you to find out what the UN’s relationship is with Iraq, with Saddam Hussein.’

‘Are you crazy! This is deadly serious stuff. This is high-powered politics!’

‘Relax. We simply want you to find out what projects the UN is negotiating with the Iraqi Government. They are helping us, but we believe they are also helping Saddam Hussein. How are they helping him? What support are they giving him? It’s vitally important to know everything about the relationship between Saddam and the UN. We have others working to this end, but you have, what shall I say, an advantage.’

‘I still don’t understand what this is all about.’

He slumped back into his chair. ‘If the UN is involved with Iraq in, say, a project like the very one you and I have been negotiating—the pipeline—we need to know about it.’

‘I see—so you can blow it up and then it will turn his army onto the Kurdish people and they’ll all get gassed again.’ The sarcasm in my voice shocked me and startled him.

‘Will you do it?’

‘Do what? I still don’t know what you’re asking me to do.’

He smiled. ‘Get close to this man David. Read his documents. Find out who they are from. Find out who he is in contact with. That’s all we need to know.’

‘I won’t do it. I’m not a spy, for God’s sake. I’ve been betrayed by others and I won’t….’

I stopped myself, but he finished the sentence for me. ‘Betray him? How can you betray someone you hardly know, Latifa?’

It was a good point. I had thrown myself onto David at the beginning because I believed he could help me escape and then I had begun to have feelings for him. But I didn’t really know him. Even so, I was not going to spy on him. I wasn’t going to spy on anybody.

‘I’m sorry, Zana. You can sack me from this job for all I care. I won’t do it.’

‘Think about it overnight. You know me. You don’t really know him. I’m offering you the chance of leaving Kurdistan if you just do this small job for us.’

That night I couldn’t sleep. Zana had virtually confirmed my earlier thoughts that my mother was a spy. She had all the attributes. Yes, Baian was attractive, she could speak English, Kurdish, Arabic and German.

She was, in fact, the perfect spy.

Now they wanted me to take up her work, not on the same large scale, but work as a spy nonetheless. Could I really betray David after he had promised to help me? Who should I place my trust in—him or Zana? Two offers of help to get out of this place. If I made the wrong choice who knew if the chance would ever arise again?

I sat up in my bed and put on the light. It was close to three o’clock in the morning. My eyes went around the room, to all the furniture my mother and father had acquired when they were young. It was dark and heavy, custom made from hard wood. Even the mattress had been theirs—similar to a Japanese futon, packed so tight with lamb’s wool that there was no ‘give’ in it and it had taken me some time to become accustomed to it after the soft mattresses of Australia and Germany. I wanted no part of their life, as it had been then, or now. I just wanted out.

I remembered a phrase from a book I had once read about espionage in the Soviet Union during the Cold War. How British spies had been lured into giving away secrets by beautiful women working for the KGB. Zana wanted me to play the same role against David. He called it a mission for Kurdistan, but I knew it by another name.

A honey trap.

NINE

My grandmother kept chickens in a cage in the back garden. There was also a rooster, which roamed free. She wouldn’t allow the rooster and the chickens to get together because she was coy about sex, according to my aunt in Baghdad. It was the rooster’s crowing that woke me a few hours later, along with the honk, honk, of a donkey some people along the street kept.

I stared at the concrete ceiling, etched into which was a floral pattern, the only concession to anything vaguely attractive in that grim room. From the ceiling hung a fake chandelier, powered by electricity, which would fail every three hours at indeterminate times. If it happened during the day, my grandmother and I would have to wait for my father to come home from work so he could use his strength to pull the cord and start our small generator.

It was with a heavy heart that I made my way out to the lounge to eat breakfast. I had made up my mind what I was going to tell Zana. I just prayed it was the right decision.

My aunt collected me as usual, stopping by the house in the company’s car. On the way to the office my whole body was trembling. Zana’s words from the previous day swept through my mind. He could even get me out without a passport, he had said. Mixed with this memory were words my father had used many years previously in Australia: ‘Always remember, Latifa, to treat people as you would wish to be treated yourself.’ Time and again those words had returned to me throughout the early part of that morning, warning me against spying on David as I had asked myself whether I was beginning to fall in love with him, or fall for him because I’d seen him as some kind of saviour.

I was trapped in a kind of mental no man’s land, between betrayal of, and infatuation for, the man from the United Nations. Had my mother been as confused as me when she had been ‘approached’? I still had no absolute proof that she had been involved in espionage—just Zana’s suggestion of it and her mysterious behaviour, flying to and from London, making numerous trips to Kurdistan and clearly holding sway with men in high places. She had been playing a dangerous game and now I had been asked by Zana, whose company I had decided was merely a front for more sinister activities, to take similar risks.

‘I’ll do it,’ I said when I entered his office. ‘But I’ll only do it on one condition. That you will give me your word you will do everything in your power to get me out of Kurdistan when I’ve done what you want me to do.’

‘Of course I’ll do that,’ he said. ‘You have my word.’

‘So what do I do?’

‘Give me a day or two and I’ll let you know.’

I hardly remember much of the rest of the day. My emotions rose and fell. Which was more important for me—betraying someone or escaping from Kurdistan? Selfishness won that mental argument. I knew I would lose my mind if I remained there for much longer. Or lose my life.

The following day was Friday. Mosque day. Everything was closed, like Sundays in the West—or rather like Sundays used to be. I spent the day dreaming of what I would do when I was free. In the closet where I kept my clothes was a drawer with a key—a key that I’d found in the lock when I had first arrived and which I’d hidden to prevent those nosey aunties of mind probing through the few things that I held precious.

There was a small diary in which I’d scribbled some of my thoughts since I’d arrived, as well as some drawings of houses and trees that my little sister had sketched and given to me when we were still in Germany. As part of my daily idlings, I had sketched things around the house—a section of wall, a corner of the building, a copy of the design on the carpet. These images depicted my cloistered world. How I wished I could stroll down the street and sit sketching the scenes—the men in their track-suit-like clothing or kaftans walking by; the various styles of the women, the Muslims in their hijabs and long dresses right down to the ankles and the As

syrians in their more Western attire; the donkeys, the scooters, the children rolling hoops through the laneways. But, as always, it was not allowed. A young woman who lived next door had given me a fashion magazine to read—brought to her from a friend visiting from Europe. She asked if I could keep it for her because her family would be furious if they found it. There was something even more dangerous she asked me to look after for her: a CD of a sexually explicit movie. There was nowhere in her house where she could either watch it or keep it, but I said I’d be able to hide it for her. So it went into my ‘secret drawer’. Heaven help me if any of my relatives were able to open it and one of my male cousins who had a CD player put the disc on.

I had by now made good friends with the group of four sisters living directly across the street—girls my father and grandmother allowed me to visit from time to time, as long as I quickly dashed across the narrow roadway, which was really little more than a lane. All houses in the street were crammed together, with families virtually living on top of one another. The youngest of the sisters was 16 and the oldest was 24, a sad woman because she wanted to get married but so far nobody had asked her because, truth be told, she did not have the beauty that men craved. She was olive skinned and the lighter your colour, the greater your chances at marriage. In contrast to Western tradition, the chubbier a girl is, the more suitable she is in the eyes of a suitor. This woman had given up school early, too, in order to train as a good housewife but the offers of marriage had failed to come in. Shilan, the sister I was closest to was the third oldest, two years younger than me, and she had the purest outlook on life—she never criticised anyone and gave the impression of being utterly honest.

I tried to visit them whenever their parents were out, when we could talk freely. They enjoyed listening to me telling them about Australia, about kangaroos and koalas and animals they had only seen in picture books. Like me when I was in my late teens, Shilan it turned out, knew absolutely nothing about sex, except having the general knowledge that after a girl was married she began to have children. I began to teach her about the birds and the bees, much to her astonishment and amusement, and how important it was for her to be absolutely certain she did not allow any man to touch her before she was married. I did not tell her what had happened to me.

Betrayed

Betrayed