- Home

- Latifa Ali

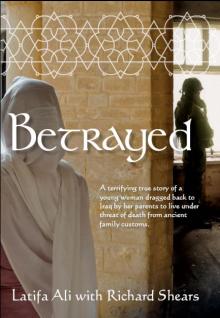

Betrayed Page 14

Betrayed Read online

Page 14

I wasn’t surprised by that. I had already concluded that Zana’s company was a government front. But I also now realised that part of my spying mission was to find out what David was thinking in terms of the pipeline project. The mission would not have related to that alone, however. Many of the documents I had seen concerned other projects within Iraq itself and Zana and his compatriates had wanted to know about everything for their own political reasons.

‘David, you cannot risk your own position for my sake. You have to be professional and you must recommend the other company. It would be entirely wrong to suggest Zana’s company solely because you want to see me. Don’t worry, we will work it out. We will find a way to keep seeing each other.’

But even as I spoke those words, I wondered how. We made love again and I cried because I worried that this might be the last time.

When, three days later, Zana learned that the company had failed to win the pipeline project, he moped about the office and kept away from me. It was as though he was blaming me for the failure because it was I, after all, who was in regular touch—for all the wrong reasons—with the UN man who made the decision.

The loss of the project caused turmoil within the office. My aunt suddenly announced to me that we were going home early—and that we would not be returning. Ever.

On the way home, I asked her what was going on.

‘It’s none of your business, but I’ll be working for the government on a rebuilding project. That means that your job with Zana is over. If I’m not going to be there, you’re not going to be there.’

‘But that’s not fair. You decide to leave and you kill my job. That’s not right at all.’

‘Your father will not allow you to continue working there without me. It was because of me being employed there that you got the job in the first place. Now it’s over.’

I was so distressed that as I made to get out of the car at my father’s house and she asked if I was going to kiss her goodbye, I said: ‘You should give yourself a kiss for the success you’ve had this afternoon.’

I was embittered because not only had a rift come between David and me with the loss of the project, the loss of my job—my only link with him because he knew where to ring me—had now become a gaping chasm. I was now standing on one side and he, and my grasp at freedom, was on the other. And what of Zana’s promise to me? A promise, on the Koran, that he would be able to get me out of Kurdistan without any documents. How was I now to contact him unless he came to me with news? But I knew in my heart that wasn’t going to happen. Well, he had sworn on the Koran to help. God would know whether to punish him or not.

When my father returned home from work I told him what had happened. ‘That’s very good,’ he said, adding, ‘that your aunt has got a good job. She’ll be very happy working for the government.’

He made no comment on the loss of my job, except to say that it would be good to have me home again during the day because I could help my grandmother with the house. There was no suggestion at all that I could continue at the company. It went without saying that my employment there was over.

The following day, to my amazement, Zana and one of the company owners—who I was certain was more than just an ‘owner’ or director—came to the door when my father was at home. They asked for me to be present when they sat down to address him.

‘Brother,’ Zana said to my father, ‘I hold great respect for you and I come to speak about your daughter. Latifa is a very good asset for our company. She is very efficient with the computer, with the paperwork and in answering the telephone. Her language skills are unequalled compared to anyone else we have ever employed there. We would like her to continue and we will ensure that at all times she is safe in our care.’

He had hardly finished when my father began shaking his head. ‘I appreciate your comments, but it cannot be. Without her aunty, there, she cannot be there.’

Zana started again while I was sent away to bring tea, but my father kept his head down—a sign that no matter what they said to him, the answer would remain no. They could implore him all morning but that hung head would be a constant negative. It was obvious to me why they wanted me to continue working there. I had proved to be their perfect spy.

Zana tried a different tactic. ‘Latifa has proved herself to be so efficient that I believe she has been offered a job as an interpreter at the UN. Perhaps, brother, that would be a good opportunity for her. Her efficiency, with respect to you, should not be wasted, and the money is good.’

‘She’s not being wasted,’ my father said, raising his head at last. ‘You know and I know, brother, the reputation those women have. The money is not important. You can never buy back a lost reputation, no matter how pure she remains.’

‘What if she had a relative in the UN? Would that make a difference for you?’

‘No female relative of mine will be lowered to work for them. Even if there was a cousin there, I would still not allow it.’

Zana nodded, conceding he was getting nowhere. I was astonished that this conversation was taking place in front of me, as though I wasn’t even there.

When at last I escorted the two visitors to the door, I managed to whisper to Zana: ‘Please don’t forget your promise to me.’

He looked puzzled. ‘What promise?’

My heart sank.

TWELVE

In my room I wanted to scream and scream, but I didn’t want anyone to hear what I knew they would consider a sign of weakness and victory—theirs. So I pulled a rag across my mouth and buried my head in the pillow and yelled and cried out. It wasn’t the first time, a reaction to my feelings of utter rejection and despair.

After a while I decided to call Zana, who would by now be back at the office. My father had gone out so I seized the chance to hurry across to my neighbours’ home. I told my grandmother, as usual, I was just going to ‘see the girls across the road for a minute or two’. Even so, she went out into the garden to check that the boys weren’t on the neighbouring roof before she gave a nod of assent.

When I knocked on the girls’ door they were surprised to see me, asking if I was supposed to be at work. I explained what had happened and that even the offer of a UN interpreter’s job had been turned down by my father.

‘Oh, you wouldn’t want to work for them,’ said the oldest sister. ‘The women who work for the UN have a very bad reputation.’

So even they had heard. I suggested it might just have been a bad rumour that had spread without any foundation and that they should give the women the benefit of the doubt. Then I asked to use the phone.

When I was put through to Zana I asked why he had not worked harder on my father to get my job back. ‘You should know, Latifa, that when your father says no, he means no.’

‘What about your promise to me? You seem to have forgotten all about it. Yet you swore on the Koran you would help me.’

There was silence for a few moments, then he asked me to call him back in five minutes. The sisters could see the frustaton on my face, although they had not understood my conversation, which had been in English. When I called Zana back, he assured me the promise still held good and that I would still be able to work for him in the meantime. That meant, of course, I might be able to remain in touch with David, even though the pipeline contract had failed to materialise.

‘But what about my father?’ I said. ‘You saw how negative he was so what makes you think he’ll change his mind when you go back to him?’

‘It’s a new proposal altogether. There’s an opening for you in Erbil. There are other women working there. Your father will approve if he knows you’re in the company of women.’

Erbil, he explained, was the town east of the large city of Mosul where the Kurdistan parliament was located and where there was a more open attitude to the West. ‘It will take you away from the restraints of your family,’ he said.

‘How is that going to be possible?’ I asked. ‘My father will not accept me livi

ng in a different town.’

‘The only way, then, is for you to just leave… just slip away with us.’

‘Who’s “us”?’

‘The company, of course. You will be in our care. There will be plenty of jobs you can do, similar to what you’ve been doing here.’

‘Oh, you mean—‘

He cut me short before I could use the word ‘spy’. But he went on to say that Erbil was also the town where Arab politicians talked to the Kurds.

‘What do you want me to do this time, Zana, sleep with Udai and Qusai, Saddam’s sons?’ I asked bitterly.

He laughed at his own reply: ‘Oh no, of course not, but if you do sleep with Arabs, don’t kiss them on the ears because that’s where they put poison. But listen, sister, seriously, do your best to persuade your father. You will get your own car and apartment. I don’t mean that you will have to drive your car because that would be expecting too much, but you’ll have your own driver. If you can do this last thing for us, you’ll be home safe in Australia very soon.’

Something told me to turn this down, even if I could talk my father into starting work for Zana again. I thought the chances of him agreeing were against me and even asking might infuriate him when he would have expected me to know how he would react.

It happened that my aunt Hadar from Baghdad, who I got on well with despite that lecherous husband of hers, was visiting Dohuk and I asked her if we could go to tea somewhere together while she was there. We found a small place where we could talk, on the pretext to my father and grandmother that we were going to do some shopping.

I told her about Zana’s proposal and asked her advice. A strict Muslim who received all her guidance from the Koran, she said that before I approached my father I should turn to the Holy Book. It would give me the answers I sought. There were two answers, of course. Should I approach my father and if there was a positive response, should I accept Zana’s offer? The Koran would tell me, she assured me, telling me to open it at random and if my eyes fell upon a surat (verse) that was in any way negative—whether it talked about punishment, things that were frightening, anything that I understood to mean a ‘downer’—to see that as a message not to even ask my father. But if the surat was cheerful, talking perhaps about God having a river of honey in paradise or referring to angels, then I should speak to my father about the job offer.

It seemed crazy to me, that my future should depend on the fall of a page, but that evening I brought down a Koran from its resting place on top of my closet—the book must always be kept in a high place if possible—and sat with it on my knee. When I had first arrived in Kurdistan my father had given the book to me, each page divided into three colums. The first was the Arabic script, the middle column was the pronunciation and the third was the translation. I closed my eyes and opened it, placing my finger on a page. The words told how disbelievers would be burned in hell fire.

That was no good, but anxious to get that job I thought I would try again, in case I had accidentally let a page slip through my fingers and had missed more positive verses. The second time was another reference to sinners burning in hell, with a particular reference to women who showed their hair or cleavage. Tere was a reference there, too, to Lot’s wife who turned into a pillar of salt as she fled from Sodom and Gomorrah. That was enough. I wouldn’t speak to my father.

I called Zana from the neighbours’ phone and told him that on divine guidance—which surprised him—I could not take the job. He urged me to think again and even offered to get a mobile phone to me so that I could call him if I changed my mind. He was obviously eager for me to go to Erbil but I was also aware that I could be letting myself into something particularly dangerous this time. Otherwise, why all that shooting practice and fast driving lessons?

‘Don’t throw away your chance,’ he said and I realised he was referring to my hopes of escaping. But a wave of doubt had come over me. I had done his dirty work for him once and now he was dangling the ‘escape carrot’ again in return for another ‘mission’.

‘Zana, I’m sorry, but I don’t feel I can trust your promises any more. I’ll think about it, but I doubt whether I’m going to talk to my father about this.’

I remained in my room for much of the following two days, coming out just to eat. George W Bush was gearing up for war and it was a topic on everyone’s lips but all I could think about was my own broken heart over the possibility of not seeing David again and also the job in Erbil that I had failed to follow up on with my father. I was so confused. And I was still trapped, with mothers still calling by with offers of marriage from sons I could not even recall ever meeting. This place, this whole region, was a madhouse.

David would have been wondering what had happened to me as I hadn’t been in touch since losing my job. I had considered calling him from the neighbours’ but I knew that hearing his voice would have only added to my frustration at not being able to be with him. Finally I talked myself into it.

‘Latifa, what’s happened. I called your office and they said you didn’t work there any more.’

When I explained the situation, he urged me to be patient; there would be a way of us seeing one another. I asked if there was any more news for me about leaving but he said I had to continue to be patient. Patient, patient. I’d had enough of being patient. Every day brought new misery and fear. ‘Please, please, David, try to do something. Have you not been able to contact anyone? Surely you could just pick up your phone and call the Australian Embassy in Baghdad. I can’t do it from this phone—its got a bar on making long distance calls.’

He said he was still working on it, but he’d been flat out and he needed to talk to me in detail about my background and have my passport number ready when he contacted the embassy. I hadn’t yet passed those details to him. I arranged to call him the following day—and I had thought up a scheme that might urge him to work more quickly on my case, while bringing me closer to him.

It had been several weeks since we had first made love without using any protection.

‘David… I think I’m pregnant.’

The silence I expected followed.

Then: ‘Are you sure, Latifa? It seems so… soon.’

‘It may seem soon but I’m late.’

‘I see.’

What he said next really shocked me.

‘Are you sure it’s mine?’

I exploded. ‘What do you mean by that? What kind of woman do you think I am? I love you, David, I haven’t been with anybody in Iraq, if that’s what you’re suggesting. Just because I was raped back in Germany doesn’t mean that I’m anybody’s. You’ve really hurt me.’

He was apologetic. ‘I’m sorry. It’s come as such a shock. We obviously need to talk about this. I’ve got a very important assignment that’s going to tie me up for the next three days. Call me in exactly four days and we’ll take this further.’

Once again I felt like a heel. But was my scheme beginning to reveal David’s true feelings? He was obviously very fond of me but he had never told me he loved me. Then again, I had never said those words to him, either, but he must surely have guessed that I was just crazy about him, despite my betrayal in spying on him. I remained stunned at his suggestion that I had been sleeping around. Had he forgotten how difficult it was to even see him on occasions?

I called his office as arranged on the fourth day, only to receive another shock. David was in Jordan. He’d left two days before—and he wouldn’t be back for a month. I refused to believe that he had skipped the country to wait out confirmation whether or not I was pregnant. But the thought lingered at the back of my mind.

I found out he had returned to Dohuk after four weeks when I saw him on the 6pm local news. He was shown talking to the local mayor about all the building projects the UN would be sponsoring around the city. When I called him the first thing he asked was:

‘Are you pregnant?’

I told him I was not. But ironically, I had been late that month, until things

returned to normal. He apologised for rushing off to Jordan so suddenly but an urgent matter had come up and he had no way of contacting me or leaving a message specially for me. I wondered about his excuse, but my love for him overwhelmed my doubts. We agreed that I would work out a way of seeing him. It might be days, it might be weeks, I told him, but he could expect me at any time.

Winter was setting in. Snow covered the mountain tops and a cruel wind swept through the narrow streets of Dohuk bringing rain and sleet. Now many of the men were wearing scarfs, too, wrapping the woollen pieces of cloth around their heads and faces—a taste of what women had to put up with every day of the year! George W Bush was beating his war drum and Saddam Hussein was remaining defiant.

An older cousin, Areeman, would come to stay with us for a few days, replacing my grandmother with the cooking chores when my grandmother was away visiting relatives for a few days in Mosul and picking up her pension of 450 dinars a month. Along with Areeman came two of her sisters, aged 16 and 14, as well as her younger brother, who was about my age. Areeman was the daughter of one of my father’s sisters and she had had a hard time of it at school with a tummy that bulged abnormally, giving rise to constant talk that she was pregnant and a wicked girl to be avoided. The poor thing could not help her condition and had learned to live with the jibes. I enjoyed her company and when my father was out we would dress up in my bedroom in clothes we were not allowed to wear in public. One day we made ourselves up to look like seductive Arab women, seductive eyes staring into the camera I had been amazingly allowed to keep. With another cousin—making a respectable group of three—we went into town and had the film processed and watched as the pictures rolled off the drying drum to ensure that none went astray and ended up doing the rounds of the tea shops. We laughed hysterically at the pictures. For me the dressing up had been a tonic for it gave me just a taste of the life I had left so long ago, it seemed, in the West. I was now 22—another year to add to my age and another step closer to the time when my father would inevitably say: ‘You’ve waited long enough for a husband and now I’m going to find one for you.’

Betrayed

Betrayed